Stanford – The Composition Teacher

I recently purchased a new CD on the German Raum Klang label (RK ap 10122) of music by Carl Reinecke and some of his more distinguished students. Reinecke taught composition for more than 40 years at the Leipzig Academy in Germany, and his students included Bruch, Greig, Janacek, Sullivan, Chadwick and Ethel Smyth as well as Stanford. This CD includes the first complete recording of Stanford’s Four part-songs for male voices, Op. 106, as well as music by the students listed and Reinecke, who was himself a prolific composer.

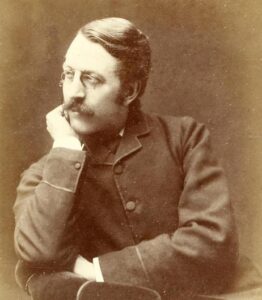

For many years after his death Stanford was remembered more as a teacher of composition at the Royal College of Music (RCM) than as a composer. From 1873 to 1876 he had studied composition for six months of each year in Germany. He went first to Reinecke in Leipzig and then to Frederick Kiel in Berlin. At the time they were probably the best teachers of musical composition in Europe. Stanford thought that Reinecke was somewhat old fashioned in his approach but said that he very much benefitted from his time studying with Kiel who he described as “ that most delightful of men and most able of teachers”.

When Stanford became Professor of Composition at the RCM in 1883 he felt it important that there was a strong orchestra where composition students could hear their work run through. He took over as Chief Conductor and the lead trainer of the College’s new orchestra and conducted it for almost forty years. He encouraged his students to both play in the orchestra and try out their orchestral compositions with it.

Some commentators have suggested that Stanford’s teaching of composition was “ without method or plan”. I very much doubt that he would have lasted 40 years teaching composition at the RCM if this was the case. I would suggest that on the contrary Stanford worked hard to develop an appropriate study plan for each of his composition students that helped them to develop technique, build on their natural gifts and enable them to develop self-confidence. All of his students were talented when they reached him. He worked to give each of them the tools necessary to fully utilize their gifts and compositional abilities. Each student was set exercises and asked to compose different types of music , often studying and composing in the style of works by the Classical Masters. There is no doubt that by today’s standards some of Stanford’s feedback to his students was very direct. But they generally felt that they had benefited from it. He did not try to impose any particular compositional style on his students and indeed many different approaches to composition developed amongst them.

As Stanford became older he was accused of being conservative in his personal composing style and musical taste. As Jeremy Dibble notes in his biography of Stanford (Oxford) ,“ His inability to embrace new ideas meant that the language of his own music, for all its brilliant professionalism, scarcely developed in concept after it had reached maturity in the 1880s.” He was also not receptive to the new musical ideas being developed in France and Germany from around 1900. But a study of his concerts with the RCM orchestra shows many contemporary works being performed. He was also a strong advocate for the performance of music by his own students.

In 1911 Stanford published his book Musical Composition where he laid out his ideas and basic concepts about composition. In the introduction in Chapter 1 of this book Stanford says “ To tell a student how to write music is an impossible absurdity. The only province of a teacher is to criticise it when written, or to make suggestions as to its form or length, or as to the instruments or voices for which it should be designed.” This was one of the first texts published on composition and it has had a long life as a primer on the subject.

The list of Stanford’s successful composition students is a long one, including Charles Wood, Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughn Williams, Frank Bridge, Samuel Coleridge Taylor, Rebecca Clarke, Ivor Gurney, John Ireland and Herbert Howells. Many of his students went on to be teachers of composition as well as composers.

Paul Rodmell has an extensive discussion of “Stanford the Pedagogue” in his 2002 biography of Stanford (Routledge). This includes extensive quotes from former students on his teaching methods and approach to composition. Rodmell ends this chapter of his biography by saying that “ Although one could not attribute the extent of Stanford’s influence to a design of his own making, without him the direction taken by British composers in the first half of the twentieth century might have been very different”.

There is much more to be said about Stanford the composition teacher. I hope that as we mark the one hundredth anniversary of Stanford’s death in 2024 and the one hundred and seventy fifth anniversary of his birth in 2027, that this area of his career will receive more attention.